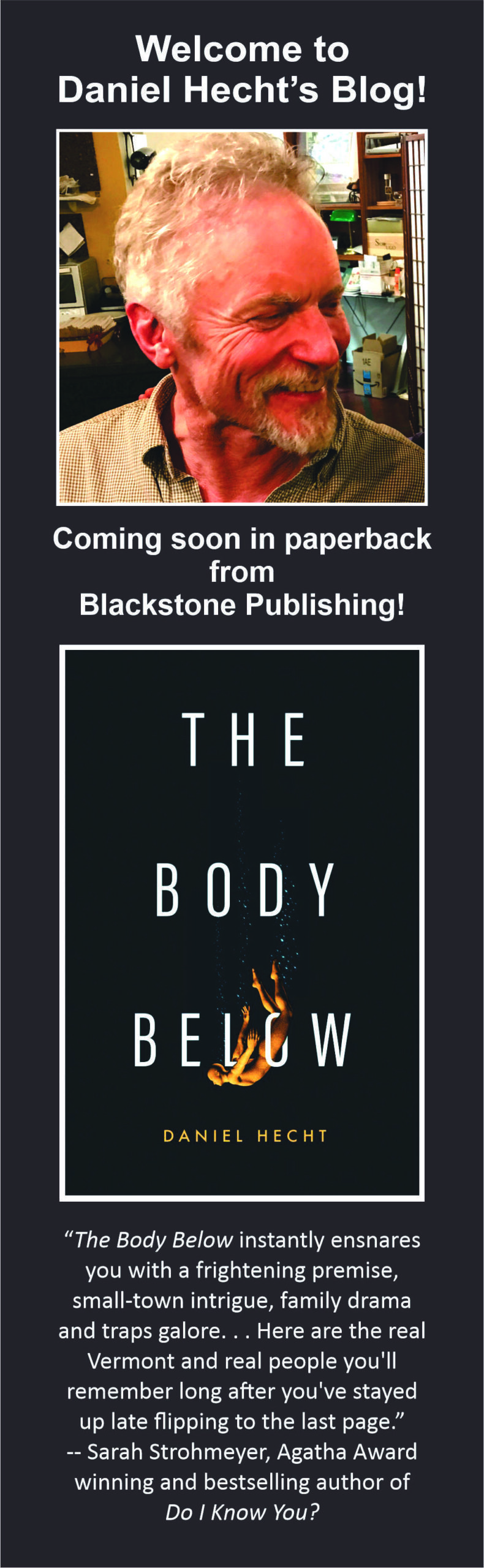

I had just begun re-posting entries from my “Meetings With Remarkable People” series when I heard that my old friend George Winston died on June 4. I was overcome by a sense of loss. We had seldom seen each other in recent years, but we corresponded often, and I could always “feel him out there” somewhere. Now, there’s a gap, a void, where his reassuring presence once was.

So I’ll write about this Remarkable Person for the next few posts — an excuse to hang with him a little longer.

Many people loved George’s music, but I suspect fewer know the extent of his other good works, particularly his tireless generosity. For over forty years, I was a frequent recipient of his kindness, which took many forms. He followed his heart and was candid about the things he loved – he was a “fan” of many people and things, and he let them know it.

In fact, my first contact with him was a fan letter I received in 1978 or 1979; I seem to remember its being written with a pencil on lined paper. I had self-published my second album, Fireheart/Fireriver — solo guitar and mixed instrumentals — not long before, and I had left a bunch at record stores up and down the West Coast, from San Francisco to L.A. This pencil-wielding weirdo from Southern California had stumbled across it. He loved it, he said, and it gave him lots of great ideas. He mentioned that he knew John Fahey, the legendary fingerpicking guitarist, with whom I also had a peripheral connection.

I had never heard of George. There was no Google back then, and anyway his album Ballads and Blues, from 1972, was pretty obscure – I hadn’t known of it even though it was on Fahey’s Takoma Records label. Still, his praise felt damned good, and I filed his letter with a very small handful of others.

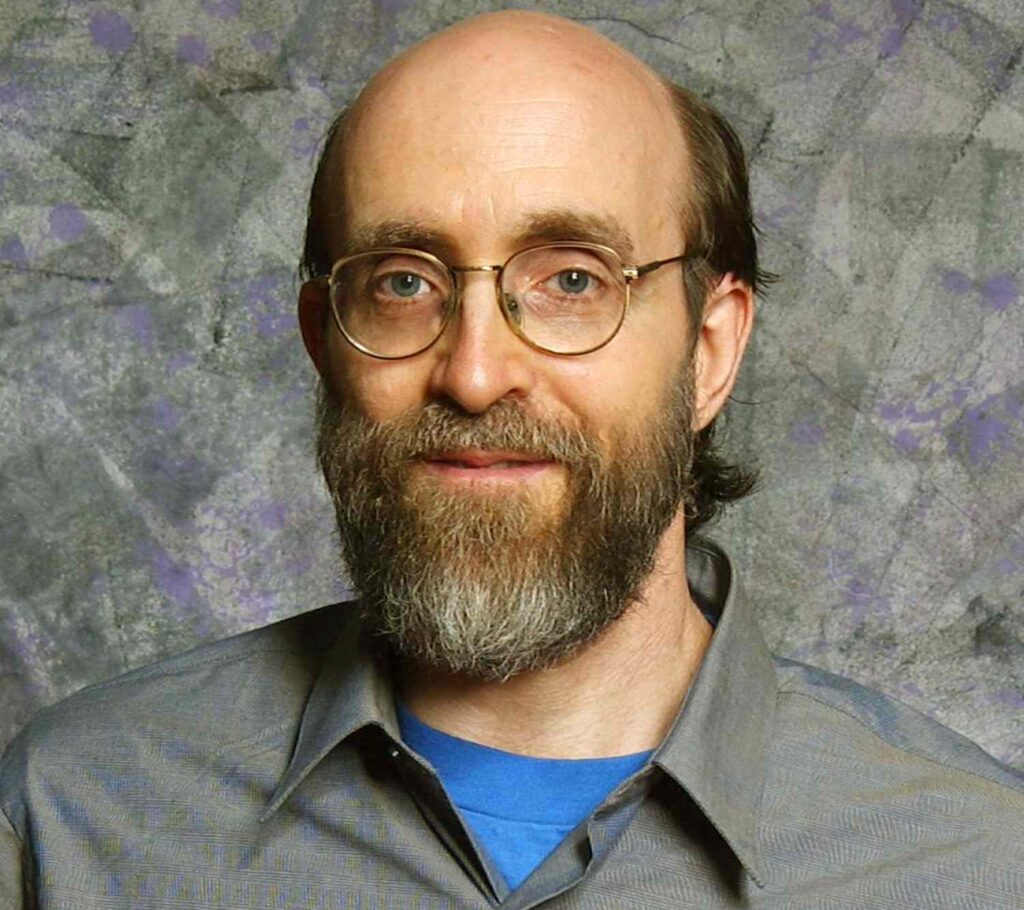

I would encounter him, indirectly, soon after. I was living for a time in Santa Cruz, and I happened to attend a concert by two solo guitarists, Will Ackerman and Alex de Grassi. Besides myself, the only steel-string soloists I knew of were John Fahey and Leo Kottke, so it was a real treat to hear two guys pursuing some of the same unicorns I chased after myself.

From a distance, we could have been triplets — blond hair of about the same length (see photo of Will from about the same period, right), and we all had the fit builds of young men who were or had been carpenters. After the show I handed them each a copy of Fireheart/Fireriver. I didn’t know Will was head of Windham Hill, but I heard from him shortly after, wanting to sign me to the label.

Less than a year later, I found myself at The Music Annex, in Menlo Park, California, recording my third album. I was thrilled to be there, and I had written a bunch of new material that I was proud of. But the experience was not pleasant for me. I couldn’t play very well.

My daughter Willow had been born in March of that year, and after assisting with her delivery — a long and uneasy process — I’d come home exhausted. Two a.m., exhilarated and brain-dead, I was playing with our cats when I made a fast grab and deflected my left little finger on a table leg. It bent sideways at the joint with a loud crack.

As every guitarist knows, your fingerboard pinkie is a crucial member of the team, and often the weakest. My years of disciplining and strengthening the digit to extend reach and perform ornaments vanished in an instant. I never went to a doctor – I was too broke to pay for one – just bandaged it and taped it to my ring finger to avoid future deflections.

The middle joint turned into a big knob, and I couldn’t fully straighten or bend the damn thing for about three years. My playing never really recovered. Thus I was not in good form at The Music Annex. Poor Will would come in to hear me record, listen to me screw up, swear, and try another take; he’d shake his head, then discreetly leave the studio, no doubt wondering whether it had been such a good idea to sign this oddball backwoods Vermont guitarist. I berated myself horribly.

In those days, even in a state-of-the-art studio like the Annex, recording was done to tape – those lovely, big metal wheels spooling slowly. Editing was done by manually rolling the tape back and forth over the playback head until the offending note went bwaaalp, then marking the beginning and end of the error with a white wax pencil. Then you’d move the tape to a special aluminum editing block and slice it at a diagonal with a single-edged razor blade. The splicing tape was white, as was the leader tape between cuts, and my master tape ended up with a good bit of white visible through the vanes of the reel.

When I cursed myself, my engineer – Russell Bond, if memory serves — reassured me: “You should see the last album we recorded. This guy George Winston, solo piano player? He had a lot of these riffs, or grooves, but not really finished ‘tunes’ as such. Will had him record improvisations and then splice together workable sections to make whole tunes.” He showed me the master tape, and I was amazed to see that it was almost all white. (Thank you, Russell!) I wasn’t alone in the white tape club.

I hadn’t yet met George, but already he was making me feel better about myself and my music.

Next: Autumn and Italy

Thanks to Will Ackerman and Dancing Cat Records for the photos.