I can’t resist writing about Bill Lederer as the first installment of my series on Meetings With Remarkable People.

Around 1975, I was living in Plainfield, Vermont, and eking out a living by various means, including teaching classical guitar. It was my first full winter in Vermont — I had been spending summers living out in the woods and returning to Madison, Wisconsin, in the winter because I could make some money there, teaching guitar or waitering. I remember it as a cold, snowy, beautiful winter.

I could stay in Vermont that winter because I had gotten a teaching job at Lyndon State College. I’d drive up two days a week from Plainfield, 45 miles each way, navigating my Chevy flatbed truck through what felt like the Arctic wilderness. I’d sit with my students in a tiny practice room, each with a pile of books on the floor as a foot stand, and we’d plunk through the lessons.

I was glad for the money and happy to have a warm, clean place to hang out, a desk of my own, and a telephone.

One day in January, the department head approached my desk and asked me if I ever took private students. He had gotten a call from somebody who wanted classical guitar lessons but couldn’t come up to Lyndon for them; he wanted them at his own house.

“I think he’s somebody pretty famous,” he told me vaguely.

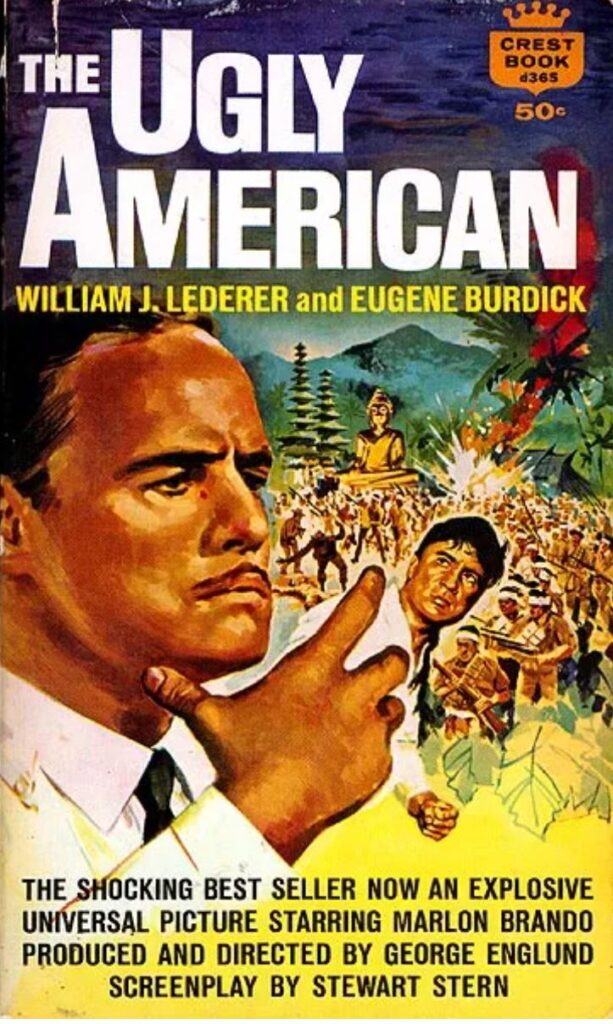

The caller turned out to be William J. Lederer, co-author of The Ugly American, a novel that in 1951 generated intense controversy its criticism of American foreign policy in Asia. He also wrote A Nation of Sheep, All the Ship’s at Sea (that’s how he thought it should be spelled, as in “at sea, we all belong to the ship we’re in”), Ensign O’Toole and Me, and many others. The Ugly American had spent 76 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and was made into a movie starring Marlon Brando; Ensign O’Toole and another book, McHale’s Navy, were adapted for popular TV shows in the 1960s.

A I knew about The Ugly American, but not any of Lederer’s other books or accomplishments. I didn’t care about them, either. I wasn’t impressed by fame, and anyway his fifteen minutes of it had come and gone a decade ago. I just needed the bucks. So, yeah, this guy was going to get guitar lessons at his home out on the back roads of Peacham.

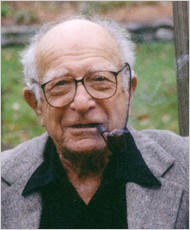

He proved to be a rare and remarkable man who became a dear friend for the next 25 years. From him I learned a great deal about accepting yourself as an unusual and contrary human being, which I certainly was, and about living life on your own terms, which I certainly wanted to do.

When I called him, the voice at the other end sounded gruff and elderly, with a stutter that required a lot of patience. The next day I drove my clanking rust-bucket over the frozen ruts outside Danville, guitar case bouncing in the seat next to me, trying to follow the directions he’d given. This was before the age of cell phones and GPS, and I spent an hour lost in the Arctic before I found his place.

It was a classic Vermont farmhouse overhung by two gigantic maples, with a big barn; across the road, a meadow opened to a sweeping view of the hill falling away to the distant church steeples of Peacham.

I crunched across the driveway just as Bill opened the door and made expansive welcoming gestures. He was of medium height, with receding curly white hair, a grizzled chin, a pipe in his jaw. In canvas pants and checked shirt, he was thickening in the middle but hardy-looking.

“Maestro!” he called. I was no maestro, and his tone was ironic, but I was flattered. He had a sense of humor, anyway.

I had been playing guitar for ten years and wasn’t much good. Any professional success I could claim was due to the vicissitudes of American culture: In those ten years, the classical guitar had gained huge popularity, thanks to the prodigious talent of Andres Segovia. People couldn’t get enough of it, and there were too few classical guitarists to meet demand. So, though I had never played in a bar or coffeehouse, by then I had played at Carnegie Recital Hall and other major venues, and had been honored as an artist in residence at a Midwest conservatory.

Bill had hot tea ready, and we sat in his living room as we introduced ourselves. He told me he lived alone; married and divorced twice, four adult kids. With his sometimes agonizing stutter, he told me of his reasons for taking up classical guitar at the unlikely age of 64 and then of his interest in a wide range of esoteric topics — dowsing, holistic health, the healing power of musical sounds, Chinese culture, unusual dietary and fitness regimens, liberal politics, a pagan belief in magics in the trees and the earth, electromagnetic fields and auras, Taoism and Buddhism.

I wasn’t sure whether these really were as important to him as they were to me, or whether he had discerned aspects of my psyche and was kindly accommodating me. I reciprocated with a comparable catalogue of interests, and I challenged him here and there, which I think he appreciated. He was well over twice my age, with experience vastly greater than my own, including a career in the Navy. Still, we found a great deal of common ground and would have similar conversations for the next 25 years.

Next: Bill Lederer II: Shaman or Sham?