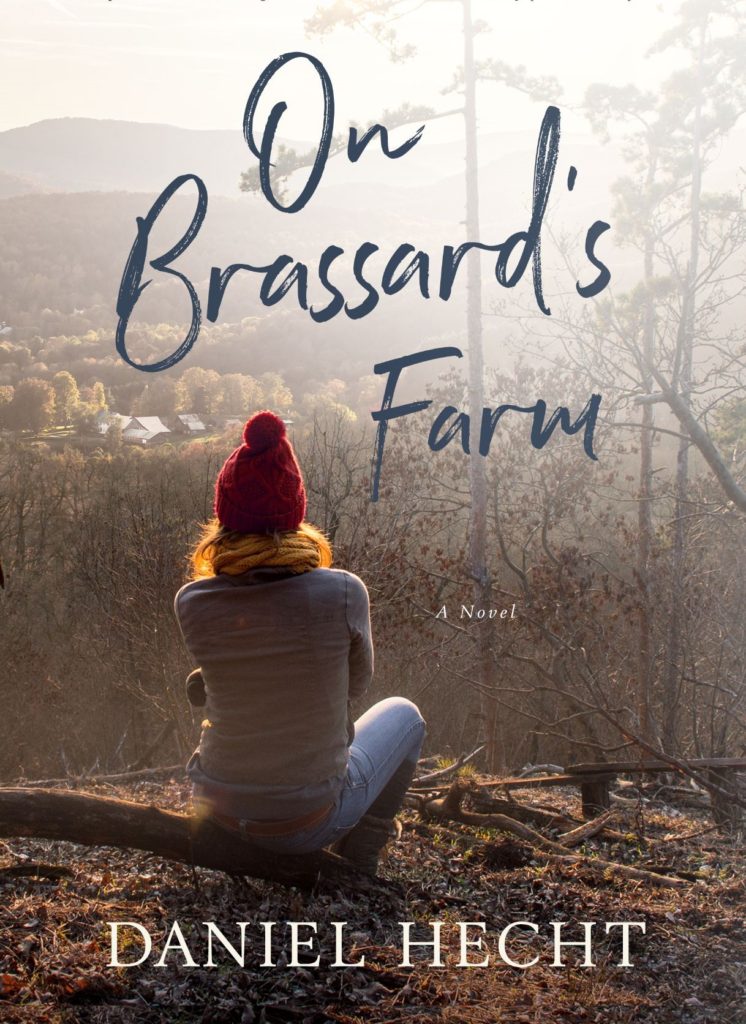

This question has been a pebble in my shoe since my latest novel, On Brassard’s Farm, was published two months ago. Notes from readers are to blame.

In my e-mail and Goodreads.com reviews, I’ve received many comments about how well – or poorly — I captured “a woman’s voice” in the story. It’s a first- person narration told by Ann Turner, a woman taking up life in rural Vermont after a lifetime as a city-dweller.

Half the comments about this aspect of the book applaud my ability to capture a woman’s thoughts and voice; half say I did a wretched job of it.

Here’s a recent complaint, from Bernadine, writing via my website: “Lacking a credible female voice. Ick.” (I love this one!) Tess, a Goodreads reviewer, wrote: “Anne definitely felt like a female character written by a man.” Goodreads reviewer Diane: “. . . the author seemed to be struggling to create a believable female character.”

At the other end of the spectrum, Mary wrote “I’m amazed at how well you wrote from a woman’s perspective — Ann is me!” Goodreads reviewer Kim gave the book five stars in part due to the “raw, rugged, and real female characters, who are to be admired.”

Another five-star reviewer on Amazon wrote “I was really surprised to find that this book was written by a man!”

Naturally, I prefer flattering comments to negative ones, but both opinions raise the same troubling question: Is there really such a thing as “a woman’s” voice?

Here’s what I wrote to Bernadine:

“First, as to my writing the book: I didn’t ‘choose’ to write it from a woman’s point of view and never once ‘tried’ to sound ‘like a woman.’ I just knew who Ann was and wrote spontaneously from inside her personality. She must be part of me, because her thoughts and words came naturally. My prior three novels, the Cree Black series, were also written from a woman’s point of view because that’s just . . . how they were supposed to be.

“The more interesting question, though, is whether indeed there is a ‘type’ of thought or behavior that’s characteristic of all women and is different from that of all men. Here, I think you’d find some resistance from many women, who don’t think females should be averaged out or collectively defined as having a particular, gender-specific mode of thinking or behavior.

“These women, and I agree with them, would find that assumption restrictive, reductive, stereotyping, and insulting. Perhaps a majority of women of a given socio-economic class or educational level or regional origin, or however one limits their background, might tend to have certain behaviors, but averages don’t necessarily apply to any individual.

“For example, the average height of American women is 5’4″. But a particular, individual woman may be 6’1″ tall and thus will have a very different experience of her body in the context of other people and any given physical activity.”

In the end, I believe that a reader may fail to like or empathize with a fictional character, but asserting that a writer didn’t understand the experience of “this type of person” sets up an uncomfortable assumption that people are defined by type or category.

I don’t believe any writer can claim to speak with exclusive authority from or to the “female” perspective or the “black” experience, the “being old” experience or the “gay” perspective. There is no such uniform, standardized experience; we are each unique.

Rather, it’s the author’s job to imagine a specific person who could be real, to engage the reader’s empathy for that character, and structure a moral thought experiment that leads the character and the reader to some new understanding. A writer may succeed or fail at this, but adherence to some presumed social “average” or convention shouldn’t be the yardstick by which this success or failure is measured.

Heidi von Schmidt, author of The House on Oyster Creek and other novels, elegantly addressed the issue when she wrote that her favorite aspect of On Brassard’s Farm was “the pleasure of seeing the world through Ann Turner’s fine-grained consciousness.” Heidi gets it right because she is speaking only of the individual, Ann, with her particular, introspective nature, not the degree to which Ann fulfilled assumptions about “gender-typical” characteristics.

I’d love to hear more opinions about the nature of “woman-thought” as differentiated from “man-thought,” and whether such differentiations provide useful guides to human nature or lead us to harmful generalizations. Can they do both?

Pondering the issue has brought me up against fascinating questions about the nature and powers of empathy, the tension between societal expectations and individual identity, writers’ goals and prerogatives in depicting fictional characters, and many more.

Please leave a comment!

Excellent, Daniel! I thought that Ann is very believable. But would I know how to write about a man, from a man’s perspective? Can I really be empathetic? Life has made me wonder about this. So far, my answer is yes and no, regardless of genders. I think that you captured Ann with many layers of depth.

Thanks, Steve. I like the question of whether one would know how to write from one’s own gender’s perspective! I, for one, know only about my experience or what I can intuit, guess, or deduce from what I see of others’ experiences. That said, I truly believe in the power of empathy. That is, I believe we can identify with others, see ourselves in others, even if they are very different from ourselves. Even though I approach things with a rationalist, scientific perspective, I think there’s a magical or telepathic dimension to the ability to intuitively “see” or “understand” others, to truly know the world as they experience it.

Can a Woman think like a Man? Can a gay man think like a heterosexual man?

Can a man or a woman think just like a human?

Now I have to read all your books! 💓

Thanks for your comment — especially “Can a man or a woman think just like a human?” I am one who believes each of us can transcend assignments of birth or society, and empathize, identify with, think like, BE, any kind of person. If not, there isn’t much hope for humanity! We’ll never get along with the”other guys”!

My protagonist Cree Black, in my prior three novels, was blessed or cursed with an extreme gift of empathy. I think many of our dividing lines are useful for analysis (looking at the pieces) but not for synthesis (bringing together the pieces into a whole). Please write again if you wish!

Well since you brought her up, will we be getting any new Cree Black stories?