Every young person needs a madman, a Loki, a Coyote, a misfit to look up to, and John Fahey filled that role for me. Long before I met him and performed with him, I knew from his writings and recordings that he must be a remarkable person.

But he was one strange critter, a study of paradoxes: a rude drunken primitive blues-influenced musician who had degrees in philosophy, psychology, and ethnomusicology.

Fahey was a pioneer of the “American finger style guitar,” the person who took the steel-string, strangely-tuned instrument well beyond the great Delta blues players who influenced him. He used many of their techniques, but to their blues sounds he added influences of Indian music, modern classical music, religious music, marching band music in unpredictable ways. His playing had a strong psychedelic effect — or at least reflected a psychedelic state of mind. It was stoned, raga-like, hypnotizing, and inspiring — as was his unrepentantly strange personality.

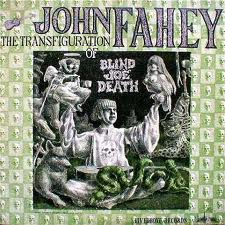

The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death. Death Chants, Breakdowns, and Military Waltzes. The Voice of the Turtle. What albums! And The Great San Bernardino Birthday Party, album and song, was transformative for me. I loved his subject matter, as his titles suggested it: railroads, industrial places, funerals, morbid ruminations, existential hard landings — no-nonsense, gritty reality, the genuine article. My favorite song title ever: “The Portland Cement Factory at Monolith, California.”

I saw him in concert only once as an audience member. My friend Glenn Johnson and I drove to Beloit, Wisconsin, to hear him play. It was marvelous — the hypnotic music and the rambling verbal extemporization between tunes, so full of elusive meaning. Afterward I introduced myself, mentioning the name of a friend we had in common — Rev. Don Seaton — and he was cordial and indicated or pretended interest in my playing.

Glenn and I drove back to Madison in the dark Wisconsin night, bursting with desire to get back to our waiting guitars.

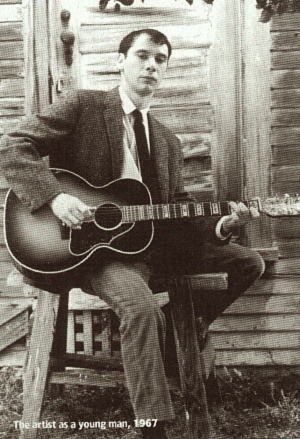

Fahey opened my mind to alternatives to the classical guitar I so loved. His strange album graphics, his extensive album cover notes that read like French Symbolist poems or novels, and that long impassive face with a touch of menace reminiscent of Robert Mitchum: too cool.

Fahey opened my mind to alternatives to the classical guitar I so loved. His strange album graphics, his extensive album cover notes that read like French Symbolist poems or novels, and that long impassive face with a touch of menace reminiscent of Robert Mitchum: too cool.

I had discovered Fahey in 1964 (thanks to my brother Nicholas), but after seeing him in concert I let myself get weirder. I had studied in conservatories, but soon I started playing my guitar in urban alleys, cow pastures, cars parked on the shoulders of highways, where I let each unique ambience come into my music. By 1970, I’d started giving my songs titles like “The Seymour, Wisconsin, Volunteer Fire Department” and “Demolition Derby.”

Ultimately, I made my first real contact with Fahey through one of his best friends, Rev. Don Seaton. Don was an Episcopal priest in whose church I’d lived and tripped. Don was at once a devout Christian and an utter pagan; he was married but bisexual, a radical lefty, and his church — on G Street in Washington, DC, the oldest Episcopal diocese in America — was ecumenical to a degree that would make St. John’s Cathedral blush. At one point, around 20 of us hippies lived in the parsonage with Don and his wife and conducted sincerely devotional but rather Druidic rites in the church at night. I remained in touch with the Seatons afterward and prevailed on their kindness when I moved to San Francisco, sleeping on their floor and borrowing their car.

Don had met Fahey years before, at his prior church, and had encouraged him in his musical endeavors; he helped Fahey finance his first, self-produced album and helped give away and sell that first run of maybe 100 copies. Fahey was grateful, and their bond remained strong until Don’s death thirty-five years later.

From Don and others I heard about his strange behavior — he was a terrible drunk and an early advocate of the prescription high — on stage and off. He wrote cryptic graffiti in the bathroom stalls of the clubs where he played. My friends and I loved his assertion of the value and power of being bizarre. Yes, you can be this far out, this far gone, and still be wise, still become a cult hero.

When I finally met Fahey at Don’s house, the three of us smoked some dope, and then while I remained silent (I was 17 and feeling out of my depth), he and Rev. Seaton carried on a stratospheric conversation full of allusions and ellipses I couldn’t follow but was very impressed by. Fahey seemed to possess secrets about life; he appeared to live by some esoteric personal code, a private Kabala that was far beyond my ken but one I though I might study and acquire musical and existential truths from.

A few years after that meeting and a few other casual encounters, I’d gotten pretty good at playing the steel-string guitar, and I conceived the idea of recording an album on Fahey’s Takoma Records label. Don Seaton reminded him that I existed; Fahey and I corresponded; I sent him a tape of my guitar solos, and he responded with enthusiasm and an invitation to visit him.

I was on the verge of a trip to Mexico; a stop at his house in Los Angeles would be right on the way.

So my girlfriend Jean and I left Wisconsin, drove our rusted-out 1963 Chevy Impala across the continent, went down the West Coast, then veered into the very belly of the beast: the sprawling wilderness of Los Angeles. It took us hours to find Fahey’s very ordinary, somewhat run-down suburban house, a grueling tour of highways and side streets and dry, bleak neighborhoods. We stood on his porch and knocked on the door with trepidation.

We needn’t have worried. Though we’d arranged this appointment, confirmed it by phone the day before, he didn’t answer the door. Not home? Forgot? Too stoned to answer the door? As Jean and I waited, we noticed Fahey’s trash, set out in large paper grocery bags. Among them were two grocery bags full to the brims with empty prescription drug bottles.

I didn’t know enough about meds to identify the drugs — I know now that he did have or get diabetes, and eventually got very weak from Epstein-Barr virus, but I doubt either was affecting him when we stood on that porch in 1973. From remarks Don Seaton and others had made, from the Legend of Fahey, I assumed they were uppers, downers, tranquilizers, sleeping pills, and pain killers.

My later contacts with him supported that assumption.

As things shook out — long and useless story — I never got a Takoma Records contract. I returned from Mexico, recorded my first album, Guitar, and released it myself. By the late 1970s, I was no longer following Fahey’s endless stream of recordings. He made 36 in all, but many were redundant compilations. After I’d heard Leo Kottke’s fingerboard sorcery, Fahey’s three-fingered, alternating-bass tunes struck me as slow, clumsy, predictable. And my own taste, style, and technique had moved on.

Still, he remained a legend, the god who birthed my steel-string playing, and his example of misanthropic individualism remained unequalled. Some years went by without contact between us.

But our paths were to cross again, giving me a closer glimpse of this astonishing creature.

Whoa!

I gotta say, I am really jealous that you were fortunate enough to spend time with him. What a rare bird he was.

It’s people like him that make this world an interesting place to live.

Thanks for sharing your stories and experiences!!!

-james scott