My last two posts in this series about “Meetings With Remarkable People” dealt with the inexplicable power of some performers to enthrall a roomful of people and hold them in a selfless state of merger with the music.

I differentiated between that magic and the “charisma” we often ascribe to celebrities and politicians. For me, musical charisma is real, a phenomenon that, in addition to its powerful subjective value, is worthy of scientific study, perhaps in the realm of cognitive neuroscience or quantum theory. The other is certainly worth scientific consideration, but in the domain of social psychology — perhaps a study of group hierarchy behaviors or hysteria.

I’ve always claimed, proudly, that I am immune to that variety.

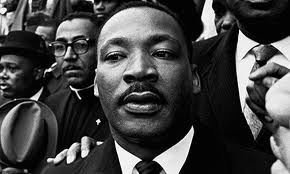

But I have to admit there is one exception for me: Dr. Martin Luther King. I wrote about this in an article Montpelier’s beloved community newspaper, The Bridge, on the anniversary of King’s birth two years ago. The first part of the article follows; the rest will follow in a future post.

I shook hands with King in Winnetka, Illinois, in 1965. My mother had recently moved us from Chicago to Winnetka because she had decided I needed better schooling, and Winnetka’s New Trier High School was considered the “best public high school in the United States.” So when I finished eighth grade we headed north fifteen miles, up to Winnetka’s tree-sheltered streets and huge houses and the cold beaches of Lake Michigan.

We were poor by Winnetka’s standards. We moved into an older apartment building overlooking the raised track of the commuter train: three rooms — my mother slept in the living room — on the third floor. No elevator, but the stairwells provided excellent reverb for a kid playing guitar in them. I daily celebrated my escape from the claustrophobic, brick-lined streets of Chicago and the rubber- and sawdust-scented corridors of Thomas J. Waters Elementary.

When your father is dead and your mother is struggling to manage four wildly inventive and willful kids as she works at whatever job she can find, your family moves a lot. Before Chicago, my mother and brother and I had lived for several years in Virginia, in various neighborhoods along Fort Hunt Road, about ten miles outside Alexandria. Fort Hunt Road left Alexandria and passed through shopping centers, then suburbs and rural districts and eventually to the outlying, less desirable places where colored people could afford to live.

By the time we moved there, in 1961, I knew where I stood on matters such as nuclear disarmament, women’s liberation, being forced to say the Pledge of Allegiance at school, China’s admission to the U.N., and civil rights. Though nuclear war was the most frightening — we were within bomb blast radius of Washington and were there throughout the Cuban Missile Crisis — racial prejudice was the more immediate issue to us.

It was of course a matter of moral principle. But its importance to us may have stemmed from our own status. We ourselves had experienced a species of bias, ever since my father’s death and our many relocations: we were perpetual outsiders, a family of artists and intellectuals and lefties who blew in like gypsies and were not to be trusted.

We were vociferous integrationists and this was the time of America’s great convulsive, agonal wrestle with its own racial conscience. When we lived in Virginia, King’s “I have a dream” speech was still some years in the future; Alexandria’s public schools were still segregated; my brother Nick was expelled from Mount Vernon High because he started an alternative school newspaper that advocated integration. Mayors and state representatives openly admitted affiliation with the Klan, and local newspapers occasionally reported lynchings. All-black chain gangs worked on the ditches and culverts along Fort Hunt Road, overseen by shotgun-wielding, horse-mounted white sheriffs.

This was hardly the “deep” South. And yet, even as late as 1984, when Alexandria won the All American City Award from the National Civic League, a large banner was hung over the main thoroughfare: “The Ku Klux Klan Welcomes You to Alexandria, the All-American City!”

About five miles from our house was a district known as Gum Springs. Chew on the name, say it with a Southern accent, and you’ll get a good sense of the place: Gum Springs, Virginia. For all I know, it’s a paradise of mansions and parks now, but then it was a hamlet set on flat, low-lying, sparsely-forested land. The scattered one-story wooden houses were shabby and many were built on stilts because without sewers and storm drains Gum Springs flooded after a hard rain.

This was where “the coloreds” lived, and where whites sometimes went to burn houses and terrorize people. It was common for new graduates of nearby high schools to drive through, shooting into the air and honking and generally sowing fear and pain. Gum Springs was barely two miles from Mount Vernon, George Washington’s estate — an irony not lost on us — but was not on any tourist’s itinerary.

In those days, black people were kept by various tricks from voting — one well-known technique was for a poll-worker to wedge a pencil lead under her fingernail so she could cross off the name of a black voter as she handled the ballot — and many more were simply too demoralized, intimidated, or disengaged to register.

But we Hechts firmly believed in the power of the ballot box. So my mother and Nick and I tried to get Gum Springs people to register to vote; I can’t remember if it was our own little registration drive or if we did it as part of some larger effort, perhaps by the local Quaker group. I liked the sense of virtue that came from going door to door, but what I mainly remember is the pathos and squalor and the suspicion or outright fear we saw in the faces of those who answered our knocks.

Driving there in our old Ford station wagon, my mother would be watchful and tight-lipped. She was afraid the wrong white people might notice us.

The point is that four years later, in 1965, in Winnetka, as a freshman at New Trier High School, I knew where my commitments lay. Winnetka was Republican in voting habits, Caucasian in makeup, and very wealthy, but its people were sincere believers in civic betterment. One of the earnest “homemakers’ associations” there, striving to stimulate local discussion on the issues of the day, invited King to speak, and of course I had to attend. More in the next post.