I first heard Michael Hedges’s Breakfast in the Field when Windham Hill Records sent me a copy (vinyl) upon its release. By then, my Windham Hill record, Willow, had been out for two years, and during that time I’d been doing a lot of concerts with Alex de Grassi, both in the U.S. and Europe.

(Alex was and is one of the most amazing musicians ever, and when he played he too radiated that rare and magical musical aura that filled a room and my mind and left me suspended, self-less, within its field. I’d do a post on Alex, but he’s still alive — see prior post — and he’d be embarrassed by all the good things I’d say about him.)

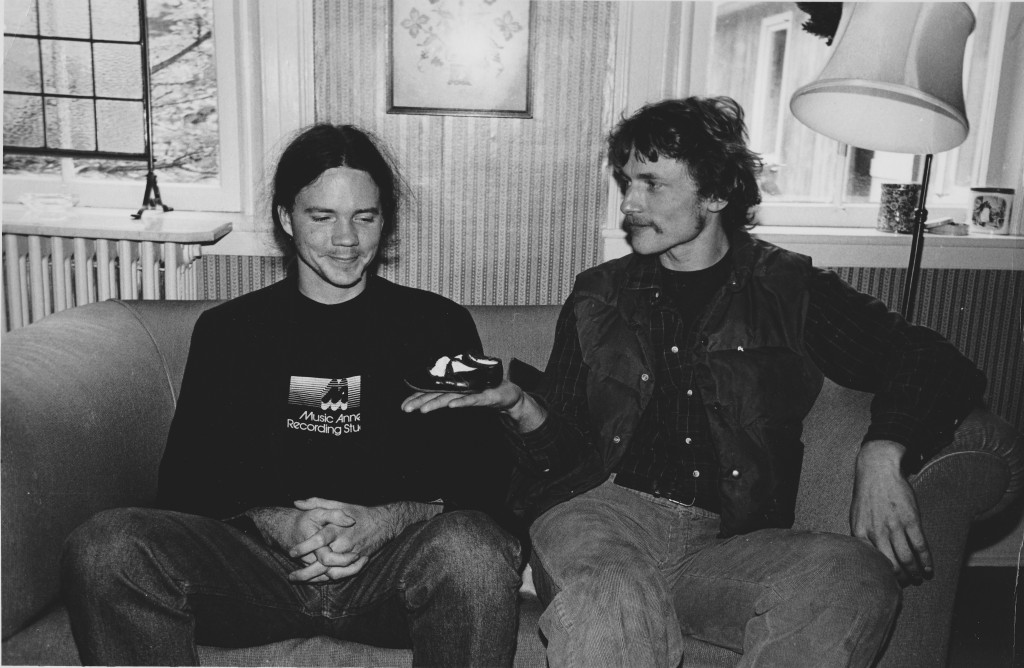

At the time, Michael wasn’t much known outside of Palo Alto, California, where he played regularly in the lobby/courtyard of the New Varsity Theater. So when his record came out, someone arranged a West Coast tour for us; I flew out and we met at our first show, a concert cafe in Seattle.

Michael struck me as wonderfully childlike — sort of shy and self-effacing. We were doing a sound-check a few hours before our performance, and as I worked on mic placement and EQ, he came to sit close by and watch me play. I looked a question at him. And he said with admiration, “I’m just watching you play. I love seeing good classical guitar playing.”

I was flattered, even though I didn’t consider myself a classical guitarist, let alone a good one. “Punk classical,” maybe.

We flipped a coin to see who had the first set. I can’t remember who went first in Seattle, but I won’t forget the experience of hearing Michael live. This guy stood up — unlike me, who sat in rigid classical guitar position — yet still controlled the guitar enough to play that complex music. And he swayed and looked ecstatic and embodied the music with every gesture. I had liked Michael’s record but wasn’t blown away; seeing him on stage, I was.

My heart broke when he sang “Holiday,” a mourning of America’s wars abroad that, at the end, segues into “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” It was too sad, a lament for a nation’s destiny lost. I never got over feeling that way; every night I’d choke back tears as Michael reminded me of the tragic paradox of our country.

Then he did some newer instrumentals that involved playing with both hands on the fingerboard and a wide range of techniques involving strumming, drumming, and “unnatural” harmonics. With its deeply-dropped bass strings and a magnetic pickup, his beat-up Martin had a big sound embrace.

Michael’s “tapping” struck many people as dazzlingly novel, a unique innovation belonging to him alone, and a whole generation of guitarists has emulated the technique. But I was not that impressed with the technique alone.

Years earlier, I had seen Celedonio Romero (the patriarch of the Romero guitar dynasty) perform a Flamenco number with incredibly elaborate, dynamic tapping, and had seen Emmett Chapman on The Stick, an electric guitar innovation designed entirely around the technique of using both hands on the fingerboard.

I liked the sound, but only as one of the guitar’s many wonderful effects. What impressed me about Michael was that “charisma.”

During the time I played with him, off and on over a couple of years, his music became more symphonic and layered, more like a weather-front than music. He increasingly let loose the rock ‘n’ roller in him — as Frets Magazine described it once, “disemboweling” the guitar.

The vehemence of his playing made me wonder how his hands survived. Classical and Flamenco guitarists, and most American fingerstyle guitarists, use the fingernails on their striking hand. I did, Alex de Grassi does, and Michael did. Even though my music was much less kinetic, mine were continually breaking, and I’d have to glue on artificial nails, or try to mend them with superglue and mesh, with generally lousy results. Michael surely had nails of steel.

So one night — we were staying at a borrowed house in Sausalito, where the eucalyptus buttons plonked on the roof all night — I asked him how he kept his nails in one piece.

So he showed me his nails, flexed them for me. I’d expected nails of horn or ivory, but in fact, they were thinner and more flexible than my own! I was astonished. How could they stay intact despite that strumming and frailing and hammering on the fingerboard? I did my own bit of tapping — there’s a bit on a video on my website, www.danielhecht.com, used in conjunction with my pedal-capo invention — and a few minutes of it could wreck my nails.

After that I watched him more closely, and found that the vehemence, almost violence, of Michael’s attack was to a large extent illusory. It was just a faster, louder version of the caress he used for most of his music (check out his right hand in one of the various videos of him playing “Holiday”). It is also of a piece with that merger of man and music: it’s a state in which miracles can happen.

One other observation that might be useful for the generation of tappers and shredders that currently rules the American guitar idiom: Michael’s greatest strength was not his ability to play fast. It was his ability to play slowly.

His ability to feel very long, very slow cycles was one of the factors that made his music so hypnotizing. It was as if, deep inside him, he had an atomic clock, keeping perfect time by sensing the microwave emissions of electrons. Perhaps this perfect and ruthless rhythm entrained our nervous systems, synched it with some cosmic constant. But if that was the origin of his effect, why doesn’t it come across (as forcefully) on his recordings?

One aspect of remarkable people: Their effect on you can transcend normal causality, the assumed laws of physics. They remind you that magic is, after all, real. That the world is, after all, magical.

I saw Michael play in Toronto in the early 80’s. I was, likewise, taken by his remarkable stage presence. What impressed the most was the clarity of the tone he was able to produce. I would learn later exactly why he was able to do that. Years later I took a class at the Wisconsin Conservatory taught by John Stropes where we attempted to learn 3 of his pieces. This was a somewhat difficult task as his music demanded a certain kind of technique that is generally not employed in more “typical” gutiar playing. Michael employed a right-hand string stopping technique, where he would sound a note with one finger and then silence it with the same finger before playing the next note. This effect, when done well, creates and incredibly clear and distinct tone absent of any unwanted sound. On the last day of the class, Michael himself came to hear our class play Aerial Boundaries (different groups of students played different sections of the piece in a round-robin fashion). We were all eager to hear what he would have to say – but at that time he was already moving away from his two-hand tapping technique and expanding musically in a completely different direction – and that was the topic of his discourse to the class – I think we were somewhat disappointed having spent a semester trying to learn right hand string stopping in conjunction with the left hand techniques he employed. He had a somewhat shy, yet unsassuming manner. During the course of the class, he would introduce and play his music for us via video tape – these were rare pieces of footage as he would play his music sitting in a chair quietly focused on the music – so unlike his concerts. At the end of the tape he would say goodbye to the class either by demonstrating how to prepare a green smoothie or possibly meditating while standing on his head, listening to AC/DC to relax. Unique individual, to be sure.

Thank you for including Michael Hedges in your ‘Meetings with Remarkable People’. There hasn’t been that much written about him since his automobile side-slipped on that rainy evening road in the coastal California mountains near his home. I wonder often if someone, or a group of someones that knew him well, will one day write his biography but then perhaps his music alone is the biography.

I wonder also if you will some day record again. Your album ‘Willow’ and Alex Degrassi’s ‘Slow Circle’ were voices in my head urging me to purchase a classical guitar and start practicing. Thank you for your music and your writing.

Thank you for commenting! I don’t know if there is or will be a biography of Michael . . . he was an unusual person as well as an unusual musician, and his tale is quite tangled in places. Alex (de Grassi) wrote an article about him; there’s a website devoted to him, but I doubt there’s anything to be learned from words, only the music. In my experience, he was receptive to many kinds of music and many musicians; when discussing his influences with me, he mainly talked about his time (and teacher, whose name I forget) at the conservatory, studying electronic music, and Neil Young, his biggest inspiration. As for me: I’m flattered that you like my playing! Ultimately, Alex’s first few albums are my favorite solo guitar records of all time (and a couple by Andres Segovia). But I haven’t played in years, and have sold my good guitars. I have a cheap classical guitar that I play once in a while, mainly to accompany my 12-year-old son when he’s practicing cello.

It wasn’t a mountain road; it was more like an embankment. I’m pretty sure I found the noted S bend (the only one) which in a quoted police report said was a mile and a half from White Rock road on highway 129. (long time ago; I went the following year, so I think it was 129, I know at the time I had the right directions from the newspaper article quoting the police report) It was the year of El Nemo (sp?) -1997 and he was driving at night during a bad storm. The police also report said his tires were not in good shape, he wasn’t wearing his seat belt, and was thrown from the car. I also imagined some steep cliff road, but was really surprised I when I found it. I also have a pic of his ’86 which I took when he played at a festival in Chico one year. The license plate says “Taproot”.

(continued) it made me very sad, as I thought he might well have survived it, if not for the condition of the car tires and the seat belt factor. Who knows?