In writing this series of posts about Meetings With Remarkable People, I’ve been reluctant to write about living ones. Why? First, I worry that the individuals I’m portraying might not appreciate my perspectives; I’m sure Nina Gitana and Bill Lederer would take exception to much of what I’ve written about them. Also, I’d hate to select among living people to assess who’s “remarkable” enough to warrant a post. My focus on one or another person shouldn’t be construed as a hierarchy of affections.

So I’ll stick to remarkable people who are no longer around to get offended. My focus this time is the guitarist Michael Hedges, whom I knew and performed with and learned a great deal from. He provides an example by which to explore a familiar, but for me problematic phenomenon, charisma.

Fidel (see prior posts) is charismatic — our neighbors call him “The King” — but charisma is a gift, not something that can be learned or earned, and thus can’t be intentionally emulated. I’m interested in what I can learn or earn.

So I don’t like the conventional idea of charisma. I have observed its effect on others, but I have never been susceptible to it, and I don’t trust it.

Charismatic people (certain American presidents and celebrities come to mind) can influence others, sway opinion, in ways utterly independent of any true intelligence, creativity, integrity, compassion, or courage that might deserve such effect. Most of the time, I believe, the experience of someone’s charisma is just a genetically-programmed social behavior inherited from our chimpanzee-family ancestors. It’s a product of our instinct to show deference to the alpha in the troupe. Worse, in groups it becomes contagious, a form of hysteria.

Our emotions are too easily molded by the dynamics of social group status. As Henry Kissinger observed — when asked why attractive women like Marlo Thomas and Jill St. John would date an outwardly unappealing, older guy like him –“Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac.”

But there is a certain kind of aura, of compelling personal presence, that manifests under certain circumstances. And it is magical.

For example, I believe that some musicians generate a force when they accomplish true unity of body and mind and music. That force can be felt by an audience, and I have felt it.

Virtuosity alone is not the origin of the effect. My mother — born in 1911, dead now — admired opera and classical music, and when she was younger she had seen both Arthur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz in concert. Both pianists are regarded as the foremost of their generation (Rubinstein was born in 1887, Horiwitz in 1903), yet they were very different in temperament, in stage presence, and in musical interpretation.

Listening to Rubinstein, my mother said, she was enveloped by the music, embraced by it, as if Rubenstein’s living, moment-by-moment experience of it were being broadcast by some radio beacon, some magnetic field, in his mind and heart. The entire audience was similarly affected; people would “wake up” after each piece, as if returning from some far-away place.

Though she found Horowitz an electrifying, brilliant presence, she considered him a musician one listened to, or at, rather than an amplifier for a musical phenomenon that the listener truly joined, became part of.

Many people have experienced this suspension of sense of self, and sense of “other,” while listening to musicians in live performance. And most are disappointed when they listen to that musician’s CD. Whatever ray or field or telepathic merge existed in the concert hall, it could not be etched into vinyl or converted to binary code.

Is there a scientific basis for this phenomenon? I’m sure there is — but science lags behind experience in this domain at present. Anyway, it doesn’t matter. What matters is the experience and what it teaches us.

I have all of Michael Hedges’ albums, and I enjoy them. But for me, listening to them has little in common with the experience of being in the same room with him while he was playing.

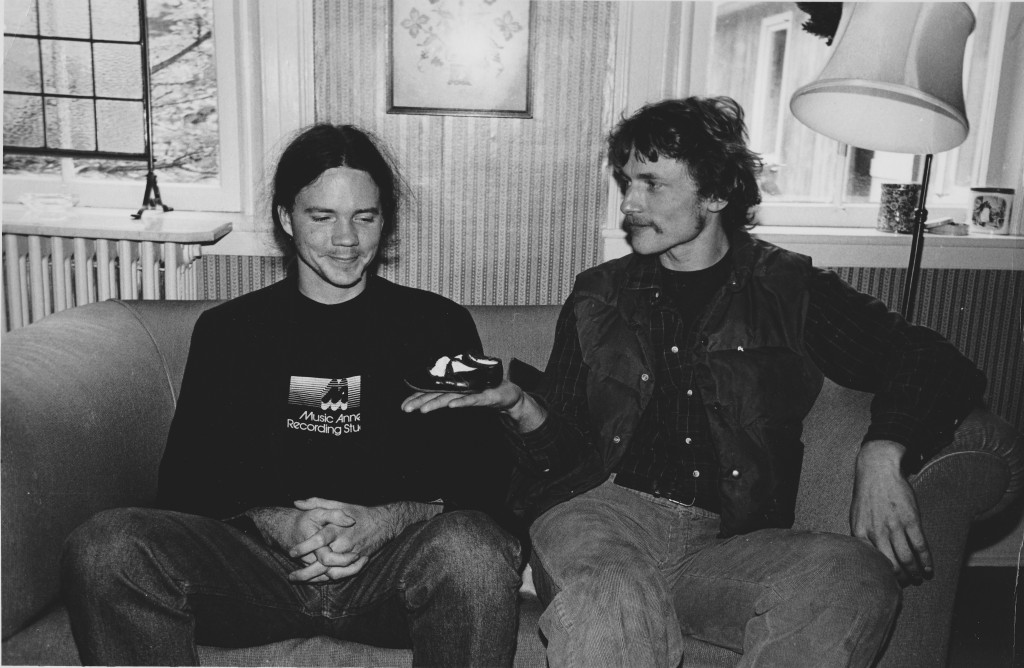

I performed perhaps two dozen concerts with him in 1983 and 1984, and I got to know him as we drove or flew from venue to venue, stayed at hotels or hosts’ homes. He and bassist Michael Manring stayed at our house in Vermont, I stayed with Michael and his wife Mindy when I was out on the West Coast. In 1984, I joined him at the Windham Hill Inn in West Townshend, Vermont, when he recorded his ground-breaking album Aerial Boundaries.

This meant that I heard him play the same pieces many, many times; you would think they’d wear a bit thin. They didn’t. Once he was on stage, he always enthralled me with his sound; each listening was as rich as the first. None of his albums capture even a fraction of the effect. Michael’s immersion in his music — standing, guitar on a strap like a rock ‘n’ roller, swaying, eyes often shut — radiated an enveloping field that allowed listeners to live completely and exclusively in the sound and in the moment.

What is the origin of this phenomenon? How does it jibe with that same person when he or she is off stage? I’ll consider Michael, charisma, and guitar technique again in my next post.