Nina’s chosen path was paradoxical.

On one hand, in her every word and gesture, she was a devotee of Kirpal Singh, whom she had met and with whom she carried on a passionate spiritual love affair. In this she resembled Rumi, the great Sufi poet and mystic, who met the dervish Shams-e Tabrisi on the road to Damascas and was so struck by him that he fell off his donkey. Forever after, Rumi’s love of the master and love of god and love of life were all one devotional passion, almost erotic — one thing, inseparable.

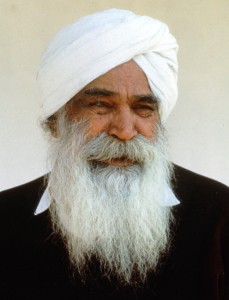

Kirpal Singh was the leader of a school of spiritual practice in which the central meditative practice, the route to transcendence, was listening to the sound current. In essence, he said, this is a thread left by God in the material world so that those seeking truth can follow it through the maze of physical manifestation to the godhead. You can hear the sound current right this instant: the faint hiss or silvery ringing in your ears that’s most audible when you are in a quiet place with no competing noises.

You can listen to it and study it for a lifetime, and your ability to hear ever-higher frequencies and ever-greater complexity will grow endlessly. When I asked Nina what her discipline was, she said simply, “I follow the Master and I listen to the music.”

Years before, I had read about naad yoga — naad meaning “the essence of all sound” — and in my untutored way had listened to that music in chanting and in silence. I knew that the world was vibratory — ordered by harmonies, just as Gurdjief had said. I had also meditated on what I thought to be my own discovery, which I called the “phosphene field” — essentially, the light current — which seemed closely linked to the sound current.

I know of no other practice that produces such transcendent personal transformation.

But I just couldn’t get the guru thing. The devotion to a Master. If Jesus and Buddha walked into my house, I’d be thrilled and probably be transformed. But I doubt I’d become their follower. My metaphysics are like those of Siddhartha, the main character in Herman Hesse’s novel of the same name, who meets Gautama Buddha yet declines to become his disciple.

Hesse’s Siddhartha believes that no philosophical system can account for the distinct, individual experience of every living being — and thus cannot replace the unique, personal challenge required to find enlightenment. There can be no guru but the self.

But Nina’s absolute devotion to Kirpal Singh was not the only clue to her nature. I recently found an entirely different glimpse of her in an entry in one of Anais Nin’s journals, from around 1955. She and “Jim” (novelist and dramatist James Agee, I believe) were at a gathering in New York at a time when the vigorous bohemian scene was flowering in Greenwich Village. Nin writes:

Nina Gitana de la Primavera, as she introduced herself, saying Gitana as if she had been born in Spain of Spanish gypsies, and Primavera as if she had been born in Italy, was utterly delirious and threw her head so far back I thought her very slender neck would break. Jim and I wanted to run away. The thread, the fine thread by which we held on to ordinary life, was in danger of being broken by this trapeze artist of words and gestures who made such perilous jumps between images and thoughts. . . .

. . . . We sat at a bar. Nina never ceased talking except to stare into our faces, or to touch our faces as if she were blind and seeking to find the contour of our features, or to gesture like a Hindu dancer loosely jointed or to say: “I talk too much.” When Jim asked her “Do you know Anais?” she seemed surprised at this question and answered “I live with the Becks. I acted in Gertrude Stein’s play and Rexroths’s.” And then I remembered an evening where the whole cast had been overtaken by hysterical laughter and the play was almost ruined. Could it have been she? Of course, she never ceased acting but I wondered how they had succeeded in placing others’ words in her mouth when she had her own overflow and profusion, but she did quote Shakespeare and Stein and mentioned Mozart and sang a tune . . . .

. . . . Jim asked her: “Say something I will always remember.” She meditated, was silent, and then gracefully and calmly made five gestures which paralleled but did not imitate the gestures of Balinese dancers. With her small, delicate, fragile hand she touched the center of her throat, her shoulder, her wrist, then placed one hand under her elbow and held it there and said: “Remember this.”

There’s much more about Nina in this entry of Nin’s, all of it depicting a fountain spirit determined to be free of convention — unrestrained, spontaneous, daring, willing to be strange and even frightening. Re-reading this episode just a few days ago, I was stunned. Was not her self-introduction to Jim and Anais — her cryptic, outlandish, non-sequitur gestures, her assertive “Remember this” — was it not similar to my somersault as a memorable self-introduction?

Had I inadvertently reminded Nina of her own stubborn, youthful adherence to a personal code, of her own self-dramatizations? None of us wishes to be reminded of the excesses — or the wisdom — of our innocence.

It might also explain why, despite such a rocky start, she thereafter received me affectionately and indulged with such patience our ongoing dharma battle.

When they encountered Nina, Anais was with James Leo Herlihy, author of Midnight Cowboy, not James Agee.

I found your blog while trying to find out more about Nina, after reading about her in Nin’s diary volume V.

This is good to know . . . however, I looked up this encounter in her journals and could swear she was referring to Agee. In any case Nina was an exceptional, amazing himan bieng, challenging us to consider what our kind is capable of.