This is my second post about creativity, focusing on Stuart Brown’s study of play and its role in neurocognitive development, inventive and generative states of mind, and mental health.

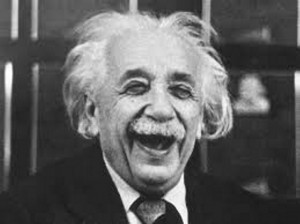

Albert Einstein, understandably, had lots to say about creativity. His summary of play’s role in generative, innovative thinking: “Creativity is intelligence having fun.”

Brown doesn’t like to define play because its nature is so widely variable and it accomplishes so many important functions. When pressed, however, he once described a number of properties he associated with play:

1) it is apparently purposeless (done for its own sake);

2) it’s voluntary;

3) it’s inherently attractive (you want to do it!);

4) it suspends your sense of the passage of time;

5) it produces a diminished consciousness of self (and an increased awareness of imaginary things and play media);

6) it allows improvisational potential (allows acting on spontaneously-occurring ideas);

7) doing it makes you want to keep doing it (continuation desire).

This catalogue is remarkably similar to Csikszentmihalyi’s description of “flow,” a highly-influential theory for the generative, innovative, creative mental state.

Historically, scientists tended to be skeptical that animals found anything intrinsically pleasurable about play. No, the animals were simply rehearsing behaviors that they’d need later in life when they’d compete for mates or look for food: chasing, fleeing, hiding, pouncing, wrestling, crudely mouthing or manipulating objects, butting heads, etc. And it is true that play experiences do teach young animals, including humans, a great deal about their physical capacities and limitations, the behavior of others of their species, and the characteristics of plants, animals, and other physical aspects of their environment.

Fortunately, that denial of animals taking intrinsic pleasure in play is increasingly seen as a relic of three centuries of often-misguided mechanistic reductionism. Ask anyone who has lived around animals in contexts other than laboratories — ethologists, zoo and sanctuary professionals, and people with pets.

Brown uses the term “play suppression” to describe the effect of environments in which young animals are deprived of opportunities for playful experimentation. For animals, this typically occurs in confinement or in highly-stressed ecosystems, and it can take place for humans in an overly-structured, parent-dominated, strictly goal-oriented home.

Play suppression has been demonstrated to produce behaviors later in life that are detrimental to survival.

In one study by Dr. Steven Siviy, professor of psychology at Gettysburg College, young lab rats were separated into two groups. Both groups received a healthful diet, but one group was allowed to play freely and to receive affectionate handling, while the other group was “play suppressed” by a variety of (non-harmful) means. Later the groups were tested to measure their capacity to respond productively to environmental stressors and challenges. You can read more about Siviy’s studies at http://www.journalofplay.org/sites/www.journalofplay.org/files/pdf-articles/2-3-article-play-and-adversity.pdf. Many other studies have produced comparable results.

This photo of juvenile rats play-wrestling is used here with gratitude to http://rappsrats.tumblr.com/post/29576040409/introducing-rats

For example, Siviy put a cat collar, full of the scent of the rats’ most terrifying predator, into the main chamber of each group’s living quarters. Both groups of rats fled to hiding places away from the cat scent, and they remained hidden even when the cat collar was removed. But the playing rats soon began making experimental forays into the danger zone. They indulged their curiosity, and explored despite possible risks. Before long, having verified that there was no danger, they felt comfortable enough to resume normal behavior.

By contrast, the play-suppressed rats remained hidden. They would have starved to death before entering the cat-scented area.

Siviy and others have identified measurable differences in brain function and chemistry between playing and play-suppressed animals. But in terms of behavior, one obvious conclusion is that play strengthens the willingness to exercise curiosity.

And, as Albert Einstein said, “The important thing is to not stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.” (You can read more of Einstein’s thoughts on fun, play, and creativity at http://einstein.biz/)

As important, according to Stuart Brown, play strengthens the willingness and capacity to measure, and to tolerate, degrees of risk. He proposes that risk-taking is a crucial aspect of play, and for this reason he advocates allowing children to enjoy their instinctive urge to engage in rough-and-tumble play.

This is a provocative idea in an era when we are highly conscious of the dangers of playground falls, of associating with strangers, of bullying, of carrying even imaginary weapons. I agree with Brown, though, that we have carried this concern too far — my nine-year-old son and his friends were put in detention for fencing with imaginary light-sabers on the school playground — and possibly to counter-productive levels.

In my next post I’ll consider mind, mud, and sticks — the importance of the latter two being a wonderful discovery made by my students at Champlain College.

Hello Daniel I Liao cheng From Liuzhou China How are you?

Cheng, it is wonderful to hear from you! I have sent other messages in reply to your comment, but have not heard back. Please contact me again.

For those reading this blog, Liao Cheng was my manager, agent, host, guide, fixer, and friend during my performance tour of China in 1989. It was one of the most remarkable experiences of my life, and I owe it all to Cheng.